Among the responses to yesterday’s post on Camp Ilchester was this suggestion:

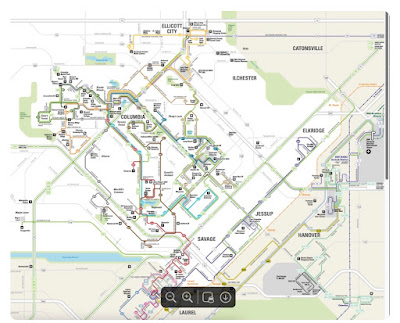

I’m hoping the County will provide public transit to it. Not seeing anything nearby.

This issues comes up a lot for me, doesn’t it? Public transit. If a place is inaccessible by public transit, we are essentially saying it is for those with cars only. Can a place truly be a public park if only a portion of the public can go there?

Speaking of which:

Here is a listing of all of Maryland’s State Parks. I wonder how many are served by public transit? And here’s an additional hurdle: fees. This website, Low Income Relief, gives you advice on:

How to Save Money When Visiting Maryland State Parks

Now, you can get in free if you are disabled or over sixty-two. If you are poor and don’t have a car? Well, you very likely can’t get there. And if you can, you still won’t be able to afford to get in.

I don’t want you to think that I have never before contemplated how poverty is an obstacle that comes between people and their ability to access good things. But it is the first time I’ve thought of it in connection with public parks. Don’t we establish and maintain public parks for the common good? Shouldn’t the “common good” include everyone?

Recently I bumped into a concept that's been circulating on the internet:

If the penalty for a crime is a fine, then that law only exists for the poor.

Essentially, the rich can pay the fine, the poor go to jail.

In the case of parks, one might say:

If a park requires a personal vehicle and an entrance fee, that park exists only for the rich.

“But I’m not rich!” you say. Well, there all sorts of definitions of ‘rich’. But, to someone without a car or the discretionary income to pay an entrance fee, that chasm between the haves and the have-nots is pretty wide. It can look mighty affluent over here from where they are standing.

Why does that matter? Consider this. A recent study found that people who spent two hours a week in green spaces such as local parks or other natural environments reported improvements in health and psychological well-being.

These studies have shown that time in nature — as long as people feel safe — is an antidote for stress: It can lower blood pressure and stress hormone levels, reduce nervous system arousal, enhance immune system function, increase self-esteem, reduce anxiety, and improve mood. Attention Deficit Disorder and aggression lessen in natural environments, which also help speed the rate of healing. (“Ecopsychology: How Immersion in Nature Benefits Your Health,” Jim Robins, Yale Environment 360)

A picnic in the park, a hike in a beautiful trail, a refreshing swim with friends or family isn’t just fun, although the ability to have fun is reason enough to seek them out. Those experiences in nature are also healing and restorative in ways that can have an important impact for everyone, most especially those who are struggling with stress, pain, and worry. Like those living in poverty, for instance.

We sometimes describe things that are easily achievable as “a walk in the park.” Or, if they’re difficult or unpleasant we say, “that was no picnic.” Yet both that walk in the park and that picnic are no more than figures of speech for many if access to public parks is primarily for the privileged.

Comments

Post a Comment